Photo by Antoine Julien, used with permission

Going toward the light?

The near-death of the Democratic Party

[Part 2 of a series that started with New Year; same hysteria and ignorance.]

Sometimes I feel o.k. but when I talk I stutter

I can’t remember back a few minutes ago

The doctors all come up with the same answer

Boy if I’m that far gone there’s nowhere else to go.

I hope that it’s only amnesia

Believe me I’m sick but not insane

Yeah, I hope that it’s only amnesia

My friends they don’t look at me the same.

(partial lyrics from the song “Amnesia” by the Pousette-Dart Band)

I continue this series by telling a tale of things most my age or older—e.g., the aged-sage™ Jane Curtin, a septuagenarian—should recall. But one particular historical sidebar may not be known by some, forgotten by others, but once known or reminded might prefer to pretend never happened. Those much younger may have been taught some of the political history, but the financial sidebar they almost certainly and universally don’t know. This series is a parable for those who have ears to hear, eyes to see, and an ability to learn from history.

The year was 1968, a presidential election year. Richard Nixon had been a political infighter going back to when he was Eisenhower’s vice president, and in the extremely close (and far from clean) 1960 election, lost to Kennedy. He seemed to disappear for a few years, and then re-emerged, invigorated, and ready for a fight when incumbent Lyndon Johnson announced he would not seek and would not accept his party’s nomination. The race was wide open.

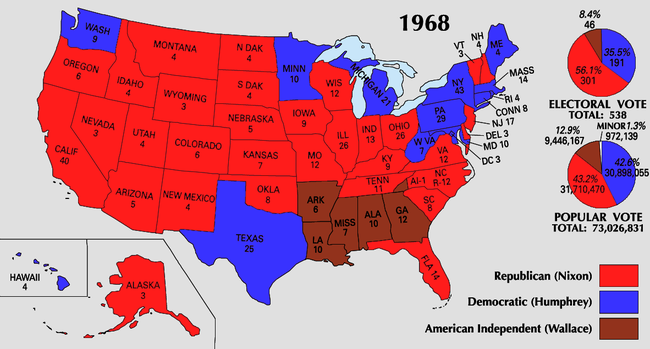

The Vietnam War was a central issue contributing to the massive social and political upheaval of the ’60s. The 1968 campaign featured Nixon (R) against Hubert Humphrey (D), Johnson’s vice president. Former Alabama governor George Wallace split off from the Democratic Party to run a third-party campaign as a candidate for the American Independent Party with a platform of maintaining the social order in the south while the region was embroiled in civil right battles of the time—another central issue, especially after the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr. on April 4 and subsequent rioting.

The Democrats held their 1968 convention in Chicago. Millions watched the various wings within the party fighting with each other, sometimes physically within the convention venue, as well as demonstrations and violence in the streets around the hall which mayor Richard J. Daley, the epitome of “vote early and often” Chicago Democratic machine politics, put down with greater violence, all of which played nicely into the Republican’s law-and-order platform.

The results:

Much has been written about the aftermath of that election, too much to include here, except to distill it all down to this: By 1970 the Democratic National Committee (DNC) was in organizational shambles and near financial ruin. Senator Fred Harris of Oklahoma who became DNC chairman in 1969, chose to use what limited funds were available to promote procedural reforms rather than organizational rebuilding of the party. Fundraising events were failing miserably. Harris resigned and was replaced by Lawrence O’Brien who, along with new party treasurer Robert Strauss, had their work cut out for themselves. How bad was the situation? O’Brien actually solicited viewers for contributions while appearing on “Meet the Press,” on March 15th (and netted around $100,000)!

By 1972, with the presidential campaign in full swing and the national convention approaching, the DNC had amassed $6.2 million of its own debt, had assumed the $1 million campaign debts each of Robert Kennedy (assassinated on June 5th) and Hubert Humphrey, plus another million from the 1968 convention for a total debt of $9.3 million (for perspective, that would be $66,600,000-plus today), and was racking up more debt at a rate of about $100,000 ($600,000 today) per month. The existence of the Democratic National Committee and the Democratic Party was in very real peril.

The usual conventional fundraising activities continued falling well short of expectations. Party treasurer Robert Strauss sought financial counsel from John Y. Brown, 38, part of an investment group that bought Kentucky Fried Chicken in 1964 (and later married Phyllis George—Miss America 1971/CBS sportscaster—and became Governor of Kentucky). Perhaps channeling Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland, who back in the day would solve such problems by saying “Hey kids, let’s put on a show!”, Brown suggested putting on a telethon.

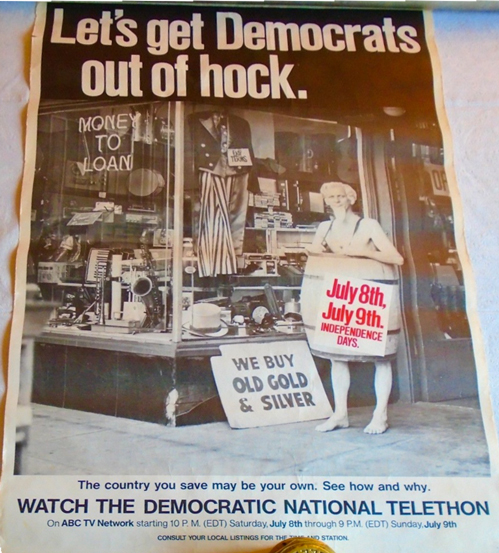

Strauss was leery: Telethons had developed a strong connection with diseases and wasn’t sure it would work. He was also concerned by the low conversion rates of turning pledges into collected revenue. Brown’s intent was to get the “little man” involved and to contribute to his own benefit. He convinced Brown and Strauss that collection rates would improve if the phone bank volunteers asked donors to charge to their credit cards (32 call centers with over 12,000 volunteers). Strauss and O’Brien agreed to go forward, so the DNC, through its Democratic National Telethon Committee (after receiving an expedited FCC prime-time access rule waiver), using the available cash it had left, purchased TV time from bid-winner ABC and produced the Democratic National Telethon.

The show would air immediately before the start of the Democratic National Convention in the hopes it would alleviate the debt but also “contribute to the harmonious atmosphere” and a hopeful sense of unity leading up to the convention.

The show would air immediately before the start of the Democratic National Convention in the hopes it would alleviate the debt but also “contribute to the harmonious atmosphere” and a hopeful sense of unity leading up to the convention.

On July 8th, Senator Ted Kennedy and wife Joan hosted a $500/couple cocktail party ($3,617 today) promoted as a “Festival with the Stars” at the Deauville Hotel in Miami Beach starting at 9 pm Eastern. At 10 pm, broadcasting began from the Deauville Hotel and the Hollywood Palace in Los Angeles, hosted by Jackie Cooper. The first hour was a tragi-comedy of errors that included garbled and crossed video and audio feeds, filmed segments that didn’t fit their allotted timeframes, and persons missing in action when they were expected to appear on air. At one point later in the telecast, a flood in the New York City area knocked out the regional donation phone bank so calls had to re-routed to Boston and Miami.

Over the course of 19 hours the telethon featured appearances and appeals from celebrities and acts rounded up by entertainment chair Ruth Berle (yes, his wife) that included Lily Tomlin, Gene Hackman, Henry Fonda, Bob Newhart, Warren Beatty, The Temptations, the cast of “Hair,” Carl Reiner, Andy Williams, Marlo Thomas, The Supremes, Dionne Warwick, Robert Vaughn, E.G. Marshall, Carol Channing, Lorne Greene, Edie Adams, Alan King, Lauren Bacall, Tony Randall, Burt Bacharach, and Groucho Marx, among others. Beatty’s sister, Shirley MacLaine, explained the call-in donation system and then gave the first donation: $10 ($72 today). I can recall watching hours of the parade of celebrities, acts, and politicians—of both parties—imploring the audience to give generously in keeping with the telethon theme of “Save the Two-Party System.”

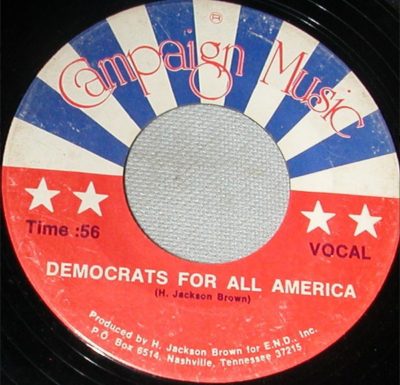

There was even an official song, “Democrats for All America,” used as the theme for both the telethon and convention, produced as a 7″45 rpm vinyl (I couldn’t find a recording, but the first 34 secs of this video might be Sammy Spear’s orchestra playing the tune at the convention). Good times!

The show ended at 5 pm Eastern the next day, Sunday the 9th. The convention was set to start in Miami Beach at 7 pm the next evening, Monday the 10th.

There were no A.C. Nielsen data for the telethon so there is no real knowledge about how many people watched what or when. The reported amount pledged was $4,461,755 of which $1.6 million was set aside to cover the cost of the telethon: $700,000 for the TV time and the rest for production. Reported estimates stated the telethon netted only about $1.9 million. Apparently, that was sufficient to relieve enough debt to keep the DNC in existence to fight another day.

For too many reasons to take up here, the 1972 Democratic convention was even more troubled than the 1968 debacle, in part, because of a seemingly never-ending series of floor fights over rules and procedures, particularly about which delegates from certain states (and the factions they represented) would be seated as members of their respective caucuses. These protracted proceedings caused sessions to run into the wee small hours, even until dawn, shedding viewers with each passing hour. One commentator noted:

The Democrats were understandably apprehensive about this convention, considering what they had gone through four years before in Chicago. It couldn’t possibly get worse than that, could it? Well, the first session on Monday night ran until 6:00 a.m. Tuesday morning. It pretty much went downhill from there. … the Democrats were committing political harikiri by pushing their nominee’s acceptance speech out of prime time…The resulting image of McGovern accepting the nomination and delivering his speech at something like 2:30 Friday morning provided reinforcement, if it was needed, of a campaign and party that didn’t know what the hell they were doing.”

It was actually 2:48 am on the final night when eventual nominee McGovern began to deliver his acceptance speech. After acknowledging the appropriate dignitaries, he began by making light of the early hour and then made two points that would come back to haunt him and the party:

I am happy to join you for this benediction of our Friday sunrise service. I assume that everyone here is impressed with my control of this convention in that my choice for vice president was challenged by only 39 other nominees. But I think we learned from watching the Republicans four years ago as they selected their vice presidential nominee, that it pays to take a little more time.

The comments were delivered light-heartedly, meant to smooth the waters after what had been a disturbing and ill-controlled national spectacle. The wheels continued to come off the proverbial campaign bus as reports surfaced that vice-presidential nominee Senator Thomas Eagleton had a history of receiving electroshock therapy for “nervous exhaustion,” and was promptly thrown under it 18 days later.

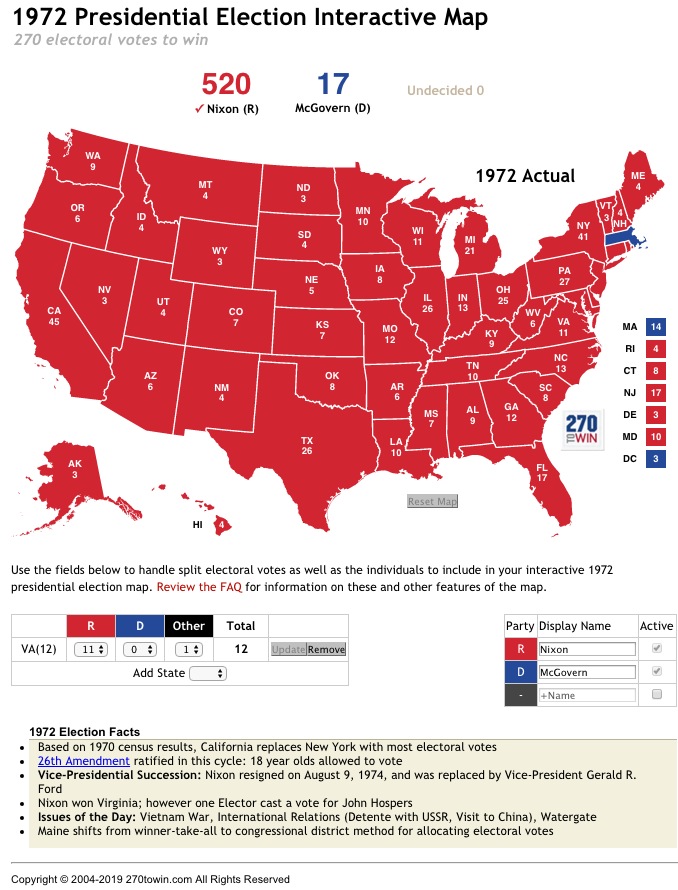

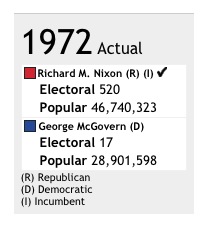

Much has been written about the self-destruction and immolation of the Democrats from 1968-1972. Nothing more succinctly summarizes the smoldering wreckage with more efficiency and impact than this:

As a 15-year-old residing in a northern suburb of Boston, and a burgeoning committed liberal typical of that time and place, the results were devastating.

The party did its own election post-mortem, formally and informally, some publicly, but more so internally. There is much to learn—for any party—from the aftermath of this part of our national political history. So-called “progressives,” so-called “democratic socialists,” and down-right communists (Sandernistas), don’t seem to have the desire or capacity to learn from their past. Neither does a significant and growing portion of anybody else professing to be a Democrat; nor indoctrinators (so-called “educators”); nor pundits of all political colors; or for that matter, an increasingly large portion of the aging general population.

But for the sake of the country, I hope that it’s only amnesia.

What were those lessons? Look for the next installment to post soon. Play me out, boys!